The American Amateur Brass Band

A Somewhat Informal Introduction

Kenneth Kreitner and the Yankee Brass Band

Pennsylvania Music Educators Association, Harrisburg, 18 July 2023

What follows is a presentation given by Kenneth Kreitner and the band at the 2023 Pennsylvania Music Educators Association meeting. A copy of the presentation is also available for downloaded here.

[The band plays Philadelphia Grays]

Good afternoon, everyone. We’re the Yankee Brass Band, as I guess you can tell: we play nineteenth-century brass-band music on antique instruments, some of which we’ll show you in a minute. Jim Chesebrough is our director, and he’ll be doing the musical side of things while I toil away humbly and I hope inconspicuously on the tenor horn. That was Philadelphia Grays, from 1839, by the great Black composer, keyed bugler, and bandleader Francis Johnson, who was born and died in the City of Brotherly Love. I’m Ken

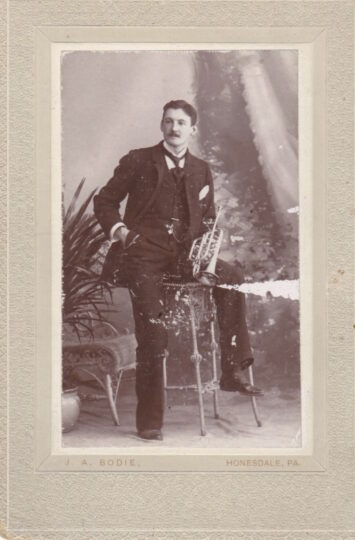

Kreitner, originally from Honesdale, up in Wayne County, in the very northeast corner of the commonwealth, and I’ve been delegated to talk a little about the American, particularly the Pennsylvanian, amateur-band tradition and what it still has to offer.

To us in the twenty-first century, the band is almost exclusively a school thing and a military thing. But in nineteenth-century America, it was above all a town thing: there were thousands of amateur bands around the country, in cities, small towns, and tiny villages,

and to the people who played in them and heard them, they were a very big deal indeed. Think back on the layer of your ancestors who were young adults between, say, 1880 and 1900: for me it’s my great-grandparents, who lived in East Smithfield and Honesdale, Pennsylvania; Oneonta, New York; and Davenport, Iowa. I suppose the Iowans may have heard visiting professional groups traveling up and down the Mississippi, but for the rest, concerts of the town band were the biggest, loudest, best-attended, and most thrilling musical events they heard most years. It is very hard to overestimate their influence on the music of this nation.

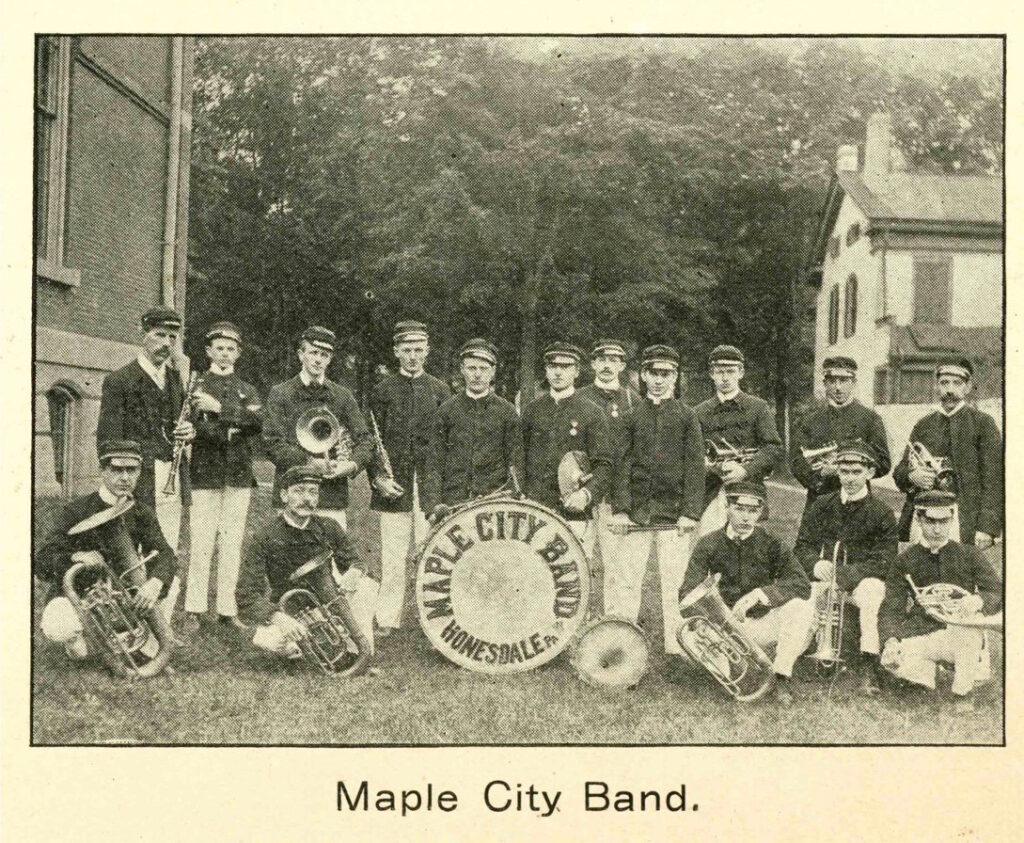

These were, I should say right away, basically brass bands, most of them fewer than twenty people, with drums and often few woodwinds, as you see here. Details in a moment, but it’s important to distinguish the amateur bands in this way from the professional

groups, like Sousa’s, which were concert bands like ours today.

The early history of the amateur tradition is hard to see, at least for me. But clearly it had something to do with the military and professional bands of the early nineteenth century; several such groups of all-brass instrumentation arose in Boston, New York, and Providence in the 1830s, and there is scattered evidence of brass bands playing in smaller towns around that time as well. These were dominated by keyed brasses—keyed bugles and ophicleides—but admitted natural trumpets and horns, trombones, and early valved instruments as available. Early publications of band music took strenuous account of this need for flexibility: a good example is E.K. Eaton’s Twelve Pieces of Harmony for Military Brass Bands, published in 1846, which included parts for E-flat keyed bugle, two B-flat

keyed bugles, cornopean or post horn, two E-flat alto ophicleides, two E-flat horns, two E-flat valved trumpets, two tenor trombones, bass trombone, two B-flat bass ophicleides, and percussion; but within that there’s so much doubling that the music could be played

with much less than the full ensemble. This practice of building flexibility into arrangements would persist for the rest of the century and beyond. So while I’m paused here, here’s Quickstep No. 8 from that collection of 1846.

[The band plays Quickstep No. 8]

Two developments around the middle of the century hastened the growth of the band among amateurs. One was the development of reliable valves and especially the adoption of the uniform three-valve system by Adolphe Sax in the 1840s, accompanied by a grow-

ing instrument-making industry, all of which made brass instruments cheaper and easier to learn and allowed players to switch around as the occasion demanded. The other was the Civil War.

Recruitment for the Civil War, as you may know, was done on the state level, and regiments were mustered locally: my great-great-great uncle’s regiment, the 141st Pennsylvania, was from Bradford, Susquehanna, and Wayne Counties, the eastern end of the northern tier. And a great many town bands, on both sides, enlisted with their regiments in the patriotic fervor. (Alas, I don’t know about the 141st.) Most of these were sent home after things got serious, but those that remained were much enjoyed by the troops during times of idleness, and fondly remembered afterward. This is the era that the Yankee Brass Band seeks to emulate: our instruments and music are mostly from the 1850s and 1860s. Here, for a specimen of that era, is Uncle Tom’s Cabin, from sometime in the 1850s, by Thomas Coates of Easton, who led the band of the 47th Pennsylvania Infantry in the first part of the war.

[The band plays Uncle Tom’s Cabin]

The war created two things: veterans, many from towns that didn’t have bands before the war but who came back with a taste for band music, and occasions—most notably Memorial Day—for them to march in public. In the years after the war, any town of any size

and pretension had to celebrate Memorial Day (different days for ex-blue and ex-gray), and a parade without a band was an embarrassment to the town, and thus the number of bands grew tremendously through the 1870s and 1880s.

Instrumentation during the Civil War period was basically what you see on the stage before you: E-flat and B-flat cornets, E-flat altos, B-flat tenors, baritones, and basses, E-flat basses, and percussion. These are the instruments we’ll show you later if you want to come up. They could be bell-front and bell-up, like ours, but over-the-shoulder horns, for marching at the head of a column, were also popular, but they’re a bit awkward in a concert situation. Anyway, around 1880 or so a subtle shift seems to have occurred, moving the leadership from the E-flat cornet to the B-flat cornet, and often adding bigger basses on the bottom.

The town-band tradition in the United States seems to have peaked, in sheer numbers at least, around the turn of the century. That’s what you’ve been seeing on the screen: a formal portrait of the Maple City band, of my hometown, Honesdale, probably on the Fourth of July 1900, standing near the Wayne County courthouse.1 It had been formed earlier that year by the merger of two existing bands; if you look closely you can see there are actually at least two uniforms in use, and the words “Maple City” are in a slightly different lettering, painted over the name of a previous band.

By one contemporary account, there were some ten thousand bands in the United States in 1889; I’m never sure about statistics like this, but I can say that Wayne County (1900 population around 30,000) had at least ten separable brass bands during the five years between 1897 and 1901, some of them in villages of only a few dozen inhabitants and some longer-lived than others. But it is clear that they were all over the place and much beloved as long as they lasted.

The end of the town-band tradition, when it came, came gradually and, I’m sure, indecisively. As the twentieth century progressed, musical tastes inevitably changed, and the generation of Civil War veterans died off, and the phonograph and radio began to produce

a superior-sounding product, and jazz arose, and the school-band movement, which emphasized larger concert bands rather than small, flexible brass bands, took on some of their role in the community. Town bands shriveled, I’m sure, by stages and winked out unseen. By the time I started playing the cornet in the mid-1960s, Honesdale did have a community band in the summer, called the Maple City Band after the men behind me, but it was clearly an offshoot of the high-school band and led by the same conductor, and we had fun but also cringed at the marches etc. that we had to play—our grandparents’ music, the worst. Only in recent years has the band music of the nineteenth century started to seem charming rather than faintly embarrassing. It is always the way.

Who played in these bands? This picture, of the same guys a year later, will give a vivid idea. (Also a better view of the repainted bass drum.) They are, first of all, guys: the town band movement was a male homosocial one, like volunteer fire companies and baseball teams. There were a few novel all-women bands around, but I have never seen a coed band from this period.2 They are mostly young, in their teens and twenties, with a few perhaps in their forties or just beyond. They are well dressed—this is a birthday picnic on a Sunday—but not posh, and I can tell you they are not the social élite of Honesdale: several, according to census records, worked in the shoe and glass factories around town and there’s also a janitor, a tea salesman, a hardware salesman, a couple of machinists, and so forth.

How did these bands happen? Well, the Maple City band was, as we’ve seen, a merger of two other bands, and those bands were themselves the products of long evolution. Honesdale (population around 5000 in 1900, and today) had brass bands, with ophicleides and so forth, as early as the 1840s, and there was probably a steadyish stream of players in town ever after, with bands forming and re-forming. But let us travel twenty miles north to Equinunk, a farming village of a few hundred souls on the Delaware River. Here we have a rather different story. A Rev. Charles Alberti, who played the cornet, arrived at the Equinunk Methodist church in 1896, saw a need for wholesome recreation among the young men of the town, and formed this band from scratch. That’s him in the middle, I guess grouchy that his clerical position forbids him to wear a uniform. And to form his band from scratch, he probably consulted the catalogue of one of the big instrument makers around the country. Among them are some familiar names, including Conn and H.N.

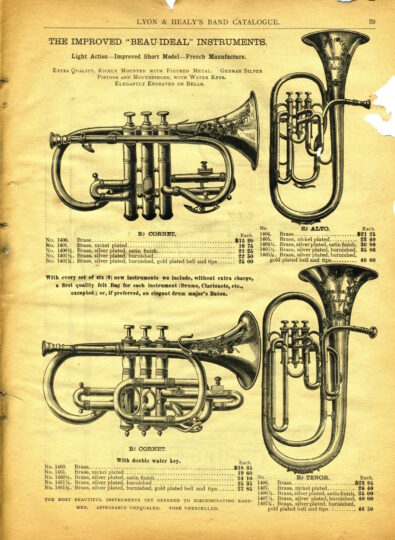

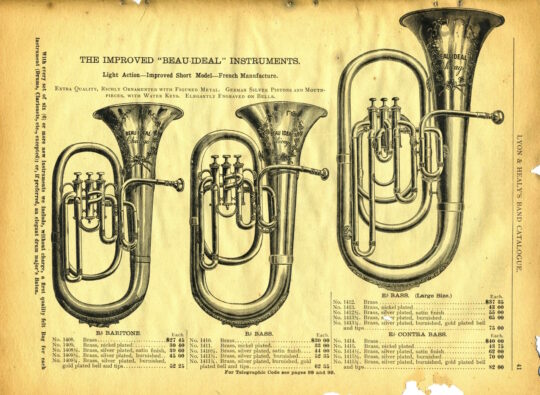

White (King to us). For our purposes here I’ll turn to Lyon & Healy, still known for their harps, but back then a major manufacturer and importer of all sorts of instruments. My slides here are from a mouse-eaten catalogue of 1901 in my collection. The holes in the page are for extra authenticity.

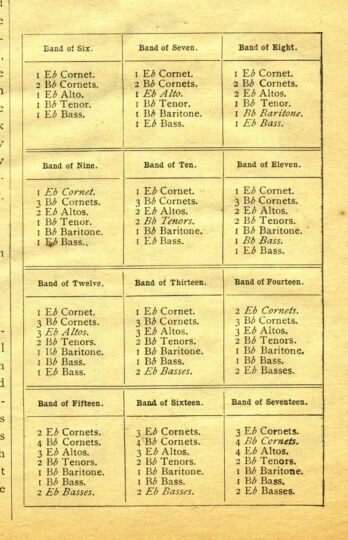

All the instrument catalogues (Sears, Roebuck too) had a table of suggested instrumentations for different sizes of band; the ones I’ve seen are similar but not identical, so they weren’t just plagiarized from one another. And the idea, as you can see, is that if you had, say, twelve people (plus drummers of course, not that they aren’t people), you would want one E-flat cornet, three B-flats, three altos, two tenors, a baritone, a B-flat bass, and an E-flat bass. More about some of these instruments in a moment, but yes, this would work pretty nicely. And as you can see, the Equinunk band doesn’t quite follow the suggested numbers, but does generally use the suggested instruments: apart from one valve trombone and a clarinet (probably he already played when the band was formed), they are all cornets and saxhorns. I bet they were bought en masse by the band. Contrast the more established Maple City band, which (in the birthday-picnic photo) has a clarinet, a slide trombone, a valve trombone, and two mellophones; these I suppose were the personal property of the players, held onto for a lifetime and played in various groups as they ebbed and flowed.

There are hundreds, maybe thousands of pictures like these out there,3 and it would be cool to count up instruments and run some stats; unfortunately, as here, it always proves frustrating, for reasons we can see when we dip down into the Lyon & Healy catalogue. These are all from their Improved “Beau Ideal” collection, one of several lines of instruments they sold.

First we have the cornets, B-flat and E-flat, and you can see the problem: unless the instrument is held just so in the picture, to expose the connection of the leadpipe and valve casings, they look very much alike. Then there’s the alto, normally easy to spot in pictures because of its size. A noble steed, the alto horn: don’t let anyone, especially horn players, tell you otherwise.

Next are the B-flat tenor (back on p. 39), the B-flat baritone, and the B-flat bass, three instruments in the same range with narrower, medium, and wider bores, but also very hard to distinguish in pictures and, to be honest, in reality: the differences are pretty subtle, as you’ll see when we show you ours. And of course the E-flat bass on the bottom.

If you have been watching closely, you may have noticed that I skipped a page, and that’s the other thing: here we see a front-pointing solo alto, three types of valve trombone, and a slide trombone—none of them countenanced by the chart of suggested instrumentations. My surmise, backed up by the catalogues I’ve seen over the years, is that the table, in its noble simplicity, never changed from Civil War times, even as the industry created lots of new instrument designs and the market lapped them up. In the picture by the courthouse on p. 1 above, you may have also noticed two clarinets—B-flat and E-flat, I think—and a possible piccolo (the resolution isn’t quite enough to be sure). These woodwinds were added to bands a lot, sparingly, but often enough by 1900 to be considered standard though perhaps not mandatory, even though they too are not mentioned in most tables.

What did these town bands do? The situations you’re thinking of—parades and outdoor concerts in a park—did take up most of the yearly schedule, and as you know, many towns around the country still have bandstands surviving from this time. In Wayne County at least, they also played for dances in the winter, picnics at excursion sites, special occasions in town as they came up, and for military events like, in Honesdale in 1898, the departure of the local National Guard company for the Spanish-American War.

What music did they play? Marches, obviously, though the terminology can be confusing: what’s called a march at the end of the century (and today) was called a quickstep in Civil War times, and a march was a more stately affair. A perhaps surprising number of dances —waltzes, schottisches, gavottes, galops, and so forth—and also “concert pieces,” called “song,” “serenade,” “overture,” “medley,” and so forth. In Civil War times, there were a good many operatic medleys and arias; not so many later. Arrangements that featured a soloist, typically on cornet, baritone, or trombone, were popular, and the all-pervasive influence of blackface minstrelsy made itself regrettably known in the repertory of the town bands. Best steered clear of today……

In the early years of the town-band tradition, instrumentations were so variable that band leaders would normally write out their own arrangements, and a lot of handwritten collections (and, frustratingly, individual partbooks) survive in libraries and historical societies around the country. There were some collections and individual pieces published before the Civil War, as I said back at the beginning, but it was after the war, as bands became more numerous and instrumentation more standardized, that a huge industry sprang up to publish music for these ensembles. Some of this music is probably moldering in your filing cabinet right now. Indeed, I would guess that nearly any American band music published before 1910 or so, Sousa excepted, was likely written with an all- or mostly-brass town band in mind, and only later adapted for the concert band by doubling and transposing parts already there. The arrangements are in general pretty simple—this is, after all, for amateurs—and I can show you a reasonably typical specimen, True to the Flag, by the German band composer Franz von Blon, arranged by the ubiquitous L.P. Laurendeau, published by Carl Fischer in 1898, and played by Lawyer’s band (predecessor to the Maple City and previous owner of the drum) on February 17, 1900.

[These parts can be found at https://bandmusicpdf.org/trueflag/.]

- The solo B-flat cornet part, as you might expect, carries the main melody and includes some low-brass cues for use as a conductor’s short score.

- The E-flat cornet mostly doubles the solo B-flat but has (unusually, I think) some noodly bits in the trio, which we’ll see doubled in the clarinets.

- The first B-flat cornet harmonizes the solo; the second and third B-flats mostly provide a smooth harmony below them.

- Now down to the E-flat basses, which play the on-beats, the ooms, doubled by the euphonium-sized B-flat bass at the unison or octave, and the third trombone is just a bass-clef version of the B-flat bass.

- Playing the pahs are the four altos and the two tenors, with the first and second trombones being bass-clef versions of the tenor lines; all these off-beat instruments get occasional breaks joining in with everybody else, as in the intro and second strain.

- The baritone (with bass and treble parts) gets a lot of roles, sometimes reinforcing the others, sometimes playing countermelodies, including a marked solo at the beginning of the trio—all richly deserved by these supreme musicians.

- The piccolos (warning: normally in D-flat) and clarinets mostly reinforce the melody and, in the trio, add noodly bits that are great but not really essential.

- And finally, the drums, which I haven’t forgotten: almost always bass and cymbals (sometimes one person, sometimes two) on the ooms and snare on the pahs.

As you can see, even in this very quick survey, the lower parts are made to accommodate treble and bass players so that you can switch a player easily onto a missing part, and the whole thing has a lot of built-in redundancy to work with various sizes of band. And so it has been in my experience: this music was arranged by people who knew what their customers had to do from week to week. Here is True to the Flag, again, played in Honesdale in February 1900.

[The band plays True to the Flag.]

Anyway. I have been thinking about these men, and the thousands and thousands like them around the country, for a long time now, and I’ve come away with a terrific respect for what they accomplished in a world where instruments weren’t taught in school and where, for many of them, leisure time was scarce. A vast amount of their music is still out there, and while it may not plumb the depths of your soul—especially if, as is likely, your soul goes down any deeper than mine—all the charm and entertainment value it had for its players and audiences, it retains for us and ours. People, in my experience, like it. But what I want to say above all to you, my fellow band people, is that these musicians are our real past, and their music is our real heritage as Americans and Pennsylvanians. And remember, this is music written not for pedagogical purposes, or to win contests, or to expose kids to different styles of music. It was there to give pleasure, and it still does. I urge you all to look into it for yourselves. And with any luck, we can all turn out to be as cool as this guy. Thanks.

1 This is the picture at the top of the paper here. For more on all of this, see Kenneth Kreitner, Discoursing Sweet Music: Town Bands and Community Life in Turn-of-the-Century Pennsylvania (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1990).

2 Since the lecture, my fellow tenor hornist Chris Troiano has turned me on to the truly staggering trove of photos at http://www.ibew.org.uk/vbbp-usal.html, where my initial browsing has turned up quite a few more women than I had anticipated. Some of these appear to be special cases—Salvation Army bands, family bands, etc.—and relatively few have secure dates, so more research is needed. So I hereby retract the word never in this sentence.

3 Later: see footnote 2 above.